To examine and/or biopsy upper parts of the gastrointestinal tract doctors commonly use thin flexible telescope known as endoscope. This instrument possesses the camera, so that a gastroenterologist (a specialist for digestive system) can look into the esophagus, stomach or duodenum and see different problems that may have caused certain symptoms.

In most cases, endoscopy is performed in doctor’s office, but it can also be done in some outpatient surgery center or in the hospital environment, depending on the circumstances.

What Happens during Endoscopy?

Patients are usually asked to lie down on the table, either on the back or on the side (which most people prefer). The doctor monitors your blood pressure, heart rate and breathing during the procedure with some monitors attached to your body.

You will receive sedative through the vein in your arm to help you relax during the procedure. Also, the doctor will use local anesthetic spray to numb the back of your throat. Once these preparations are done, you will be asked to wear a plastic guard on the mouth and swallow the endoscope tube. There will be no pain while you swallow this instrument but it can be slightly unpleasant.

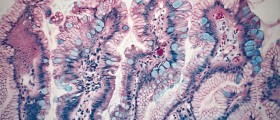

Once the endoscope is in your esophagus, doctor will turn it on and there will be a picture of your gastrointestinal tract on the monitor. Doctor closely examines the digestive tract, looking for suspicious areas or present problems. If there happen to be some polyps or suspicious looking tissues, doctor may need a sample. He/she will use the endoscope and pass surgical tools through this tube in order to perform biopsy (take a sample of the suspicious tissue), which will be examined in the laboratory.

Once the procedure is done, doctor will retract endoscope from your mouth and it is over. In general, endoscopy usually lasts for about 20 minutes, while the whole preparation and recovery may add up to 2 hours of your time.

What to Expect after Endoscopy?

Patients usually need to recover for a while after this procedure, sitting or lying down and this can last for an hour or so. During this period drowsiness from sedatives should wear off at least for a little bit, so that you can go home. Most people, however, are advised to get someone to escort them home, because sedative drugs may affect driving and operating machinery for 24 hours after the endoscopy.

Some patients may experience cramps, bloating and gas, as well as sore throat after this procedure, but these commonly improve after a while. If you happen to experience more serious problem, do not hesitate to consult your doctor. In rare cases, patients may have severe problems due to bleeding or perforation after endoscopy, while some older patients may experience heart attack or stroke (usually during the procedure).

- Pre endoscopic preparation. Premedication with simethicone or simethicone and N-acetylcysteine improves visualisation in the stomach and oesophagus. Pronase, a proteolytic agent, increases gastric visibility scores. The use of antispasmodic agents to enhance detection of high risk superficial neoplasms is recommended.

- Sedation. Patients should be counselled adequately regarding sedation options. Reported satisfaction is higher after endoscopy with sedation. A closed ended questionnaire found that patients undergoing oesophageogastroduodenoscopy (OGD) did not have sufficient information prior to endoscopic examination to make an informed choice regarding sedation option and that patient satisfaction was higher in patients who received sedation.

- Systemic examination. A mandatory set of systemic images in endoscopy reports may increase quality of reports and reduce variability in interpretation. There is currently no consensus how many pictures should be recorded for an adequate OGD. The use of systemic alphanumeric coded endoscopy approach during endoscopy increases yield of high risk lesions.

- Duration of examination. Endoscopists with average Barrett’s inspection time (BIT) exceeding 1 min per centimeter detected more endoscopically suspicious lesions; a longer BIT correlated with high grade dysplasia and adenocarcinoma detection. Endoscopists with a mean examination time exceeding 7 min for a normal examination were twice as likely to detect high risk lesions and neoplastic lesions compared to their faster counterparts. The effect of longer examination time may be diminished in very experienced endoscopists who are able to readily recognize neoplastic lesions.

- Routine endoscopy biopsy. No studies have demonstrated that routine biopsy improves detection of high risk lesions during endoscopy. Endoscopists with high biopsy rates were less likely to miss a cancer in patients who undergo interval endoscopy.

- Image enhanced endoscopy. Absence of iodine staining on chromoendoscopy, even when negative for dysplasia on initial histology, identifies esophageal lesions with high sensitivity for dysplasia or cancer in later follow ups. Non-magnifying narrow band imaging (NBI) was found to have similar sensitivity with superior accuracy and specificity compared to iodine staining for early squamous cell carcinoma. Endoscopists should be trained in the NBI use. NBI Sensitivity was higher in the hands of more experienced endoscopists. Blue laser imaging (BLI) is comparable to magnifying NBI as well as Lugol iodine chromoendoscopy for detection of early esophageal cancer.

- Future developments. Raman spectroscopy differentiates normal gastric tissue from premalignant and malignant tissue and allows real time diagnosis and reduces need for biopsy. Endocytoscopy allows real time diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori positivity, intestinal metaplasia, atrophic gastritis and early gastric cancer. There is good interobserver agreement between endoscopists and pathologists. Neural network based artificial intelligence can now be trained to identify oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma and gastric cancer with high sensitivity and specificity.

Your thoughts on this

Loading...