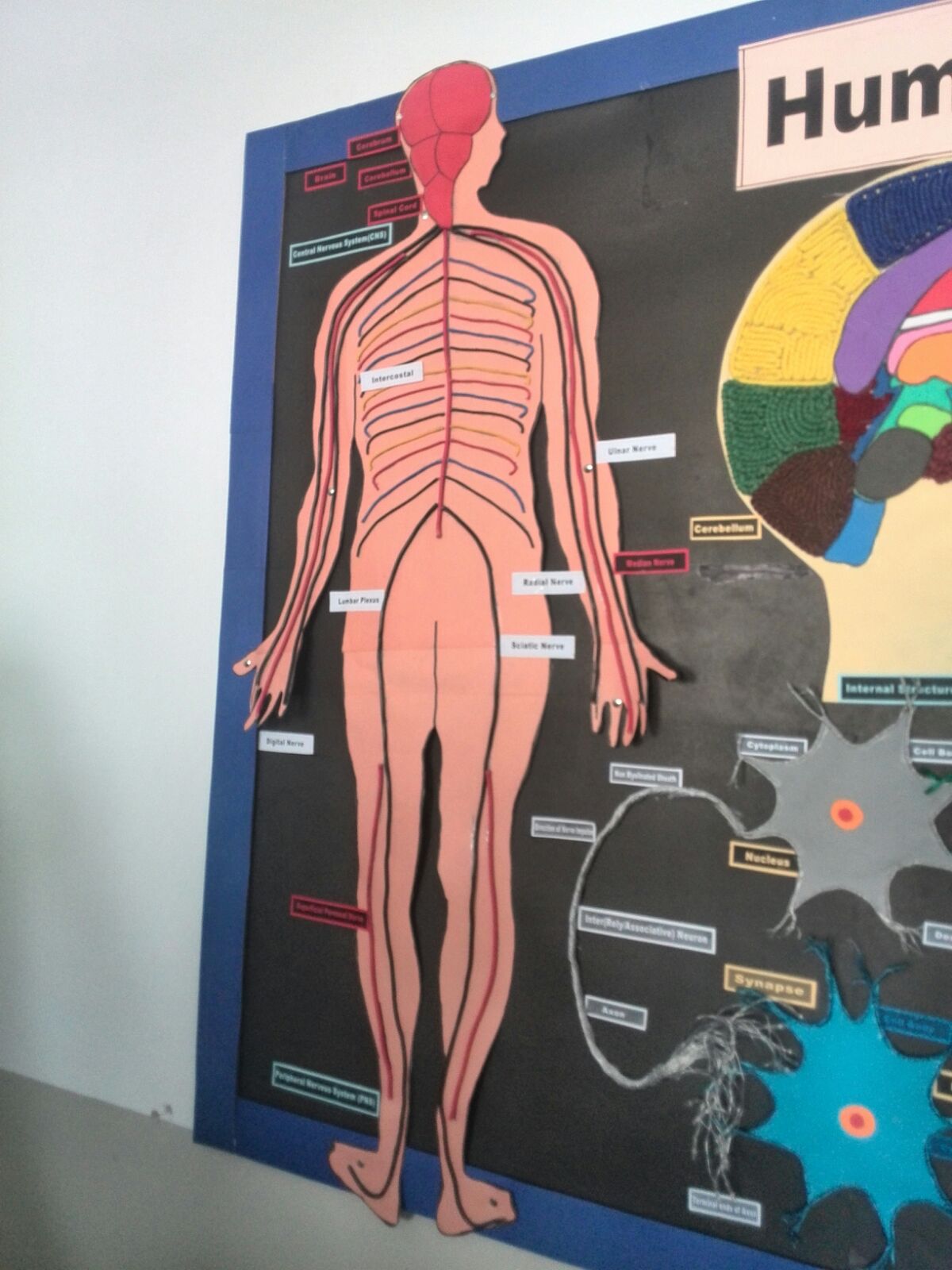

Guillain–Barré syndrome is a disorder that affects peripheral nervous system. This condition is actually an acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy characterized by ascending paralysis. Patients with Guillain–Barré syndrome usually experience progressive loss of feeling in feet and hands. This weakness gradually migrates towards the trunk and sometimes even causes life-threatening complications. The most severe consequences may occur when the disease affects breathing muscles or causes dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system. This is a rare condition that affects one or two individuals per 100,000 people each year. However, it still remains one of the most serious health concerns and the leading cause of non-trauma-related paralysis in the world.

What is Chronic Guillain–Barré Syndrome?

As already mentioned, Guillain–Barré syndrome is an acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. In most cases, patients will begin to recover after a month from the onset of the disease. In only a couple of months, most of the patients (about 80% of them) will be completely recovered. Small percentage of patients, somewhere between 5 and 10 percent, will recover with severe disability including proximal motor and sensory axonal damage. However, this is a serious condition that causes death in 2–3% of all patients. Chronic Guillain–Barré syndrome is diagnosed in patients who have one or more relapses of the disease, even after they initially recover. This chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy affects 5 and 10 percent of patients.

- Guillain-Barré syndrome is usually preceded by infection or other immune stimulation that induces an aberrant autoimmune response targeting peripheral nerves and their spinal roots. Molecular mimicry between microbial and nerve antigens is clearly a major driving force behind the development of the disorder, at least in the case of Campylobacter jejuni infection. However, the interplay between microbial and host factors that dictates if and how the immune response is shifted towards unwanted autoreactivity is still not well understood.

- The acute progression of limb weakness, often with sensory and cranial nerve involvement 1–2 weeks after immune stimulation, proceeds to its peak clinical deficit in 2–4 weeks. When patients present with rapidly progressive paralysis, the diagnosis of Guillain-Barré syndrome needs to be made as soon as possible. Although establishment of the diagnosis in typical cases is usually straightforward, there are many clinical and investigative components to consider, especially in atypical cases.

- All patients with Guillain-Barré syndrome need meticulous monitoring and supportive care. Early initiation of intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIg) or plasma exchange is of proven benefit and crucial, especially in patients with rapidly progressive weakness. Because a quarter of patients need artificial ventilation and many develop autonomic disturbances, many patients need admission in the high or intensive care setting. Symptoms peak within 4 weeks, followed by a recovery period that can last months or years, as the immune response decays and the peripheral nerve undergoes an endogenous repair process.

- Efforts focus on the measurement and prediction of clinical course and outcome to improve the care and treatment of individual patients. Good prognostic models have been developed, but additional studies are needed to investigate whether these prognostic factors differ between different disease subgroups and areas in the world. In parallel, prognostic biomarkers now need to be developed to better predict outcomes and guide action, such as personalised treatment refinements in acute management.

- The annual incidence rate of Guillain-Barré syndrome increases with age (0,6 per 100?000 per year in children and 2,7 per 100?000 per year in elderly people aged 80 years and over) and the disease is slightly more frequent in males than in females. Seasonal fluctuations, presumably related to variations in infectious antecedents, have been reported, but these observations are rarely statistically significant.

- Until 20 years ago Guillain-Barré syndrome was regarded as a homogeneous disorder, the outcome of which varied according to severity. This variation was believed to be largely caused by the extent of bystander axonal injury arising secondarily to adjacent demyelination, rather than fundamental pathophysiological differences in the types of Guillain-Barré syndrome between individuals.

- According to various diagnostic criteria for Guillain-Barré syndrome, patients can have progression of weakness within 4 weeks. Most patients, however, reach the nadir within 2 weeks. Progression can last up to 6 weeks after onset (subacute Guillain-Barré syndrome) in some rare cases. During the progressive phase, 20–30% of patients develop respiratory failure and need ventilation at an intensive care unit (ICU). The clinical condition of at least 25% of patients deteriorates during or shortly after treatment with IVIg or plasma exchange - the inference of which is that they would be worse without therapy, rather than an indication of complete treatment resistance.

Signs and Symptoms of Guillain–Barré Syndrome

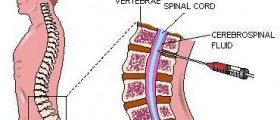

Guillain–Barré syndrome usually starts from the lower limbs and slowly affects the rest of the body. Patients may complain about rubbery legs that tend to buckle, feel numb or tingling. The progression of the disease is sometimes very rapid, and occurs in just a couple of hours. The weakness affects arms, facial muscles, and sometimes cranial nerves. In some patients it may cause respiratory difficulties so that patients may need ventilator assistance. Patients often feel deep aching pain in their week muscles, but this symptom is relatively easy treated with analgesics. In severe cases, bladder dysfunction may occur, as well spinal cord disorder. In most severe cases, Guillain–Barré syndrome is associated with fluctuations in blood pressure, orthostatic hypotension, and cardiac arrhythmia.

Causes of Guillain–Barré Syndrome

Guillain–Barré syndrome is an autoimmune disorder that occurs when body’s immune system responds to foreign antigens but mistargets the host nerve tissues instead. This way, the body attacks its own gangliosides in nerve tissues and causes inflammatory reaction. It most commonly occurs in conjunction with antecedent infection with Campylobacter jejuni bacterium. In about 60% of cases, the cause is unknown.

Your thoughts on this

Loading...