Lymphadenopathy

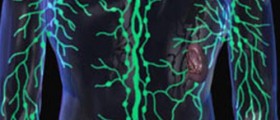

Lymphadenopathy is an enlargement of lymph nodes. Our body contains approximately 600 lymph nodes which have numerous functions. Only some groups of lymph nodes including submandibular and submental, cervical lymph nodes, axillary and inguinal lymph nodes are available for palpation and even the patient can notice their enlargement.

Internal lymph nodes can also get bigger and their enlargement usually compresses surrounding organs and tissues leading to specific symptoms. In the case of internal lymph nodes, the symptoms vary according to the very localization of the enlarged lymph nodes.

Lymphadenopathy can be painful and painless. If there is an enlargement of lymph nodes in only two or more noncontiguous areas lymphadenopathy is classified as generalized while localized lymphadenopathy refers to the enlargement of only one group of lymph nodes.

Lymphadenopathy is basically painless. Only if the affected lymph nodes become too big they can compress surrounding structures including nerves and cause pain. Painful enlargement of lymph nodes is also evident if lymph nodes are affected by certain infections.

Causes of Lymphadenopathy

Lymph nodes get bigger in a variety of infectious diseases as well as in malignancies.

Reactive lymphadenopathy is an enlargement of lymph nodes induced by bacterial or viral infections. Lymph nodes can additionally enlarge due to certain chronic diseases such as tuberculosis and cat-scratch disease.

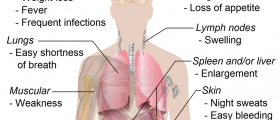

Bubonic plague typically features huge lymph nodes. They are so specific and are called buboes. The necrotic process inside the affected lymph nodes eventually leads to their rupture. Enlarged cervical lymph nodes, especially if accompanied by enlargement of the liver and/or spleen, point to mononucleosis. Furthermore, anthrax and trypanosomiasis also feature enlarged lymph nodes of the neck. Generalized lymphadenopathy is detected in toxoplasmosis.

Many tumors, primary or metastatic, may cause painful or painless lymphadenopathy. Primary tumors which affect lymph nodes include Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma as well as hairy cell leukemia. Lymphadenopathy also occurs in the secondary spread of the tumors of nearby, or distant organs. Lymphadenopathy can additionally be caused by certain autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, or sarcoidosis.

And finally, patients who are immunocompromised as well as those suffering from HIV or AIDS also develop lymphadenopathy at some point.

Painful enlargement of lymph nodes is typical after venomous snake bites.

Diagnostic Approach to Lymphadenopathy

In the majority of patients painful or painless lymphadenopathy is caused by infections. The affected lymph nodes reduce in size thanks to appropriate treatment and after a certain period of time. However, if lymph nodes tend to stay enlarged or even grow bigger even though patients are under treatment the doctor needs to perform a biopsy of the affected lymph nodes to find the underlying cause. Prolonged enlargement is either connected to chronic infections or to malignancies.

- There were several common clinical signs. The most frequent were neck swelling and erythema and the palpable cord beneath the sternocleidomastoid muscle, frequently associated with fever. Oedematous swelling of the face/scalp, papilledema and intracranial hypertension were also reported in several papers. These kinds of symptoms could be ascribed to a possible impairment of the cerebrospinal fluid dynamics, which is strictly connected to the cerebral venous outflow.

- Only 1.1% of these cases are related to malignancy, but this percentage increases with advancing age. Cancers are identified in 4% of patients 40 years and older who present with unexplained lymphadenopathy vs. 0.4% of those younger than 40 years.

- Etiologies of lymphadenopathy can be remembered with the MIAMI mnemonic: malignancies, infections, autoimmune disorders, miscellaneous and unusual conditions, and iatrogenic causes. In most cases, the history and physical examination alone identify the cause.

- Factors that can assist in identifying the etiology of lymphadenopathy include patient age, duration of lymphadenopathy, exposures, associated symptoms, and location (localized vs. generalized). Other historical questions include asking about time course of enlargement, tenderness to palpation, recent infections, recent immunizations, and medications.

- About one-half of otherwise healthy children have palpable lymph nodes at any one time. Most lymphadenopathy in children is benign or infectious in etiology. In adults and children, lymphadenopathy lasting less than two weeks or greater than 12 months without change in size has a low likelihood of being neoplastic. Exceptions include low-grade Hodgkin lymphomas and indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma, although both typically have associated systemic symptoms.

- Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) and core needle biopsy can aid in the diagnostic evaluation of lymph nodes when etiology is unknown or malignant risk factors are present. FNA cytology is a quick, accurate, minimally invasive, and safe technique to evaluate patients and aid in triage of unexplained lymphadenopathy. If a reactive lymph node is likely, core needle biopsy can be avoided, and FNA used alone. Combined, they allow cytologic and histopathologic assessment of lymph nodes. However, the use of both techniques may not be needed because the diagnostic accuracy of FNA in adult populations has been reported to approach 90%, with a sensitivity and specificity of 85% to 95% and 98% to 100%, respectively.

- medlineplus.gov/ency/article/003097.htm

- www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK558918/

- Photo courtesy of Coronation Dental Specialty Group by Wikimedia Commons: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cervical_lymphadenopathy_right_neck.png

Your thoughts on this

Loading...